Press Releases and Newsletters

Reduce crime by strengthening the state’s judicial system

The Metro Mayors are convening a Public Safety Summit on August 28th to build a consensus advocacy agenda with other stakeholders.

Seek federal and state stimulus dollars for city infrastructure needs

The North Carolina Metropolitan Mayors Coalition released a list today containing $2.8 billion of ready to go infrastructure projects demonstrating local government’s ability to put the federal stimulus dollars to work quickly on projects that will create nearly 100,000 jobs.

Download the original Federal Stimulus Package Press Release.

Perdue to attend Salisbury public safety summit (SalisburyPost.com)

Perdue to attend Salisbury public safety summit (SalisburyPost.com)

Tuesday, August 11, 2009 3:00 AM

By Mark Wineka

[email protected]

Perdue to attend Salisbury public safety summit

Download the original newspaper article.

Salisbury will be the host Aug. 28 for a statewide summit on public safety.

The summit, called “Seamless Solutions to Urban Crime,” will be held from 10 a.m.-3 p.m. at Salisbury Station on Depot Street.

Gov. Bev Perdue is expected to attend, along with N.C. Attorney General Roy Cooper, N.C. Department of Crime Control and Public Safety Secretary Reuben Young and N.C. Department of Correction Secretary Alvin Keller.

Salisbury Mayor Susan Kluttz said the day's focus will be on gang violence and an overburdened court system.

The event is part of a two-day annual meeting of the N.C. Metropolitan Mayors' Coalition, which will hold a similar summit on transportation issues Aug. 27 in Concord.

The mayors' group will invite more than 200 key players in public safety issues statewide, including sheriffs, district court judges, district attorneys, mayors, city managers, police chiefs, experts in the field, relevant state agencies, school resource officers, members of the Governor's Crime Commission and others.

Kluttz will be traveling to Raleigh Wednesday with Salisbury Police Chief Mark Wilhelm and Assistant to the City Manager Doug Paris to help in the planning for the public safety summit.

“It will be big, and we're excited about it,” Kluttz said Monday. “… This is the appropriate place for it in the state.”

Kluttz said no other community in North Carolina is as aware as Salisbury of gang problems or been more active in trying to develop youth initiatives.

A Rowan County teenager and suspected gang member awaits trial for the March 2007 shooting death of 13-year-old Treasure Feamster, who was attending a party at the J.C. Price American Legion building and was caught in a confrontation between gangs as the crowd dispersed.

The shooting served as a wake-up call to the city of Salisbury about local gang violence. It became an issue Kluttz has focused on as a member of the mayors' coalition.

Last year the Department of Crime Control and Public Safety reported 1,446 active gangs in 64 counties across the state.

At the summit, the Metropolitan Mayors' Coalition will try to develop a process and schedule for solutions that will culminate in the spring with the announcement of a public safety agenda and action plan.

In addition, it will be launching a new, interactive Web site at the meeting to encourage issue advocacy and the online exchange of ideas.

The site will include a Twitter feed and breaking news posts, allowing interested parties to stay informed and involved.

Tickets for the “Seamless Solutions to Urban Crime” summit may be purchased in advance for $25 and will be available at the door for $35. To register, visit www.ncmetromayors.com.

The N.C. Metropolitan Mayors Coalition is comprised of mayors from North Carolina's 26 biggest cities and focuses on transportation, public safety and the economy.

The organization was founded in 2001 around transit issues by a group of 15 mayors across North Carolina.

Stimulus tends to shortchange cities (N&O)

Stimulus tends to shortchange cities (N&O)

BY STEVE HARRISON AND BRUCE SICELOFF, McClatchy Newspapers

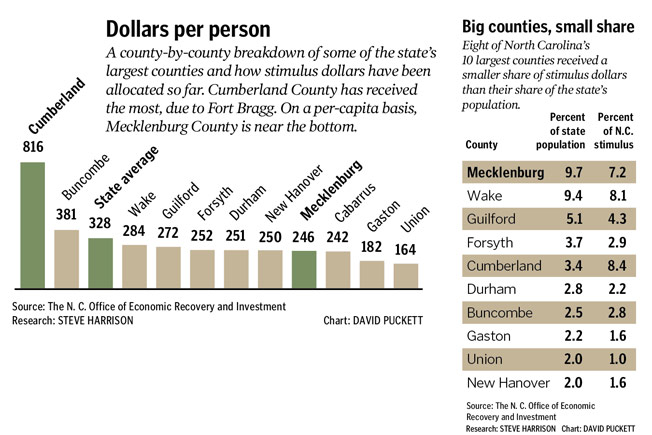

North Carolina's stimulus checkbook shows that rural counties have benefited more than urban counties on a per-person basis, with Wake and other populous counties getting less than an average share.

Federal funds allocated through June 30 under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act add up to $328 for every state resident. The per-person share falls to $284 in Wake County and $252 in Durham County.

One urban county doing very well so far is Cumberland County, home to Fayetteville and Fort Bragg. The Department of Defense has poured money into the Army base, pushing Cumberland's per-person total to $816.

Many of the stimulus dollars are distributed by existing state formulas that favor rural over urban counties, and money is going to programs that focus on certain parts of the state.

“The Department of the Interior is spending money in the mountains and in the coasts,” said Dempsey Benton, who oversees stimulus spending in the state. “That's not going to help the Mecklenburgs and the Guilfords.”

Benton heads the N.C. Office of Economic Recovery and Investment, which recently released a county-by-county breakdown of stimulus funding. North Carolina has been allocated $3.2 billion through June 30 and has spent $1.3 billion.

The state will receive at least $8.2billion in all over three years, a figure that could grow by a few hundred million if North Carolina wins lucrative grants in several areas.

The stimulus, designed to jump-start the economy and improve the nation's infrastructure, includes money for construction projects such as roads and weatherizing buildings, and also assistance payments for food stamps and school systems.

As unemployment nationwide has hit 9.5 percent, a 26-year high, Republicans have criticized the stimulus as ineffective. One problem has been that money hasn't been spent as fast as the Obama administration hoped.

Benton said there has been a longer-than-expected lag time in federal agencies issuing rules as to how the money must be spent. But he said North Carolina is moving quickly to spend the money.

Most public works projects that will use stimulus funds have not begun construction. But stimulus safety-net spending gets into the economy quickly, Benton said. So far the state has received more than $580 million for extra food stamps, Social Security Insurance and unemployment payments.

“That money has come into the system and is recycling through the community,” Benton said.

What's slated for Wake

The state's most populous counties, Wake and Mecklenburg, have been shortchanged in highway dollars because the money is distributed according to the state's equity formula, which Gene Conti, the state transportation secretary, said penalizes urban areas.

Wake has been allocated $49.8million in stimulus money for roads and bridges. The biggest single share, $13.9 million, will widen a stretch of U.S. 401 north of Raleigh. Most of the local road funds will be spent on smaller projects to repave freeways and build miles of greenway trails.

By contrast, the state DOT office overseeing five counties in central North Carolina chose to spend all of its stimulus highway dollars — $64 million — in Fayetteville. That will help build part of the city's Interstate 295 loop.

“The major issue here is that the DOT just did not have a lot of big projects ready to go in the

Raleigh will combine $7.6 million in stimulus funds with other grants to start work on a $22.5 million bus garage and operations center that is a key part of planned transit expansion over the next 25 years.

“We are very pleased with the over $35 million we've gotten for city projects,” Meeker said. “We're moving quickly to get these under construction.”

Some of the Triangle's stimulus share comes through its biggest government employers — state agencies and flagship state universities. A $39.5 million grant will build a new headquarters for the National Guard and offices for the state Department of Crime Control and Public Safety in Raleigh.

UNC-Chapel Hill, N.C. State University and Wake Tech shared $36 million in education stabilization funds to balance their budgets for the 2008-09 school year. In all, Benton said, North Carolina has received $1.1 billion to cover budget shortfalls and will get another $2.8 billion over the next two years.

Competitive bids

North Carolina will be competing for stimulus grants in categories that could bring several hundred million dollars more into the state, on top of the $8.2 billion Benton now expects. The state is in the running for a healthy share of $8 billion for faster passenger train service, and for a $300 million grant to replace the I-85 bridge over the Yadkin River at Salisbury.

The state also will bid for a few hundred million dollars in broadband Internet expansion and education grants.

Joe Bryan of Knightdale, a Wake County commissioner and a professional financial adviser, said he has not seen much evidence so far that stimulus spending is providing new jobs or protecting old ones.

“It does not appear to have had much of an impact on employment in our area,” Bryan said. “Whether it's going for education or for health issues, that's safety-net money. That's not creating jobs.”

[email protected] or 919-829-4527

###

Mecklenburg County lags in share of stimulus (Charlotte Observer)

Mecklenburg County lags in share of stimulus (Charlotte Observer)

N.C.'s largest county ranks near the bottom in spending per person

By Steve Harrison

[email protected]

North Carolina's stimulus checkbook shows that rural counties have benefited more than urban counties, on a per-person basis, with Mecklenburg's share lagging.

Mecklenburg has so far received $246 per person in federal stimulus dollars, compared with $328 per person statewide.

The one urban county to do exceptionally well is Cumberland County, home to Fayetteville and Fort Bragg. The Department of Defense has poured money into the Army base, pushing Cumberland's per-person total to $816.

Local officials are still chasing millions in stimulus grants, but some are frustrated.

“This is a nationwide trend on how the money was divvied up – everyone is getting a little bit, and in the end there will be nothing to show for it,” said Charlotte Mayor Pat McCrory, a Republican. “We should have spent it in Eisenhower- and Roosevelt-type projects for the next generation.”

Mecklenburg's low per-capita share is due to a number of factors.

Many of the stimulus dollars are being distributed by existing state formulas, some of which favor rural over urban counties. Mecklenburg has received only $8.9 million in grants – out of $409 million – distributed by federal agencies.

Dempsey Benton, who oversees N.C. stimulus spending, said there are some pots of money that are difficult for Mecklenburg to access. The Department of the Interior, for instance, has so far spent $12.3 million in North Carolina – mostly in coastal counties, and none in Mecklenburg.

“The Department of the Interior is spending money in the mountains and in the coasts,” Benton said. “That's not going to help the Mecklenburgs and the Guilfords.”

The N.C. Office of Economic Recovery and Investment, created to handle stimulus money, last week released a county-by-county breakdown of stimulus allocations through June 30. It has allocated $3.2 billion through June, and the state estimates it's spent $1.3 billion.

The state expects to receive $8.2 billion.

The stimulus, designed to jump-start the economy and improve the nation's infrastructure, includes money for construction projects such as roads and weatherizing buildings, and also assistance payments for food stamps and school systems.

As unemployment nationwide has hit 9.5 percent, a 26-year high, Republicans have criticized the stimulus as ineffective. One problem has been that money hasn't been spent as fast as the Obama administration hoped.

Benton said there has been a longer than expected lag time in federal agencies issuing rules as to how the money has been spent. But he said North Carolina is moving quickly to spend the money, and that it's above average among states in getting money on the street.

Mecklenburg has so far been allocated $219 million. The county has struggled accessing some of the biggest pots of money.

The Charlotte Area Transit System carries more than 33 percent of the transit passengers statewide, but a state formula gave it 21 percent – $20.8 million – of the transit money parceled out statewide. CATS plans to use the money to refurbish a bus maintenance garage on North Davidson Street.

Mecklenburg has been shortchanged in highway dollars, due to the state's equity formula, which the N.C. Department of Transportation secretary Gene Conti said penalizes urban areas.

Mecklenburg has so far received $37.3 million in stimulus money for roads and bridges, for projects such as widening N.C. 51 south of Pineville, improving a traffic signal system in Charlotte and widening N.C. 73 in Huntersville. The Department of Transportation's office overseeing the Charlotte area distributed the highway money and chose to spend some money in neighboring counties like Anson, Union, Cabarrus and Stanly.

By contract, the DOT office overseeing five counties in central N.C. chose to spend all of its stimulus highway dollars – $64 million – in Fayetteville. That will help build part of the city's outerbelt.

Mecklenburg has struggled accessing the third-largest pot of stimulus money – grants from federal agencies.

Charlotte/Douglas International Airport didn't get $2 million in funding for runway repairs from the FAA. No Charlotte federal buildings have received money to become environmentally friendly. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has bypassed Mecklenburg.

Cumberland, by contrast, is benefiting from $117.5 million in defense grants to Fort Bragg and Pope Air Force Base. The money will be spent on more than 70 mostly small projects, such as paving roads, improving barracks and making buildings more energy efficient.

Cumberland's unemployment rate is 9.3 percent; Mecklenburg's is 11 percent.

The state has so far used $126 million in “education stabilization” funds to help universities and community colleges pay their bills. Mecklenburg has received $7.8 million for UNC Charlotte and Central Piedmont Community College. Orange County, home to UNC Chapel Hill, has received $20 million and Wake County, home of N.C. State, has received $15.8 million.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools' share of stimulus dollars has more closely matched the county's population, but one state budget proposal would reduce state money to CMS by the same amount.

Charlotte assistant city manager Ron Kimble said the city is so far pleased with how much money it's received. But the city has a team to apply for competitive stimulus dollars.

The city is seeking nearly $26 million to hire 150 police officers, $8 million to buy 11 hybrid buses and $20 million to buy 200 foreclosed homes.

There is still the possibility the stimulus will produce the type of large, long-lasting project McCrory wants.

The N.C. DOT hopes to use stimulus money to improve rail service between Charlotte and Raleigh, increasing speeds up to 110 mph. The state is also applying for a special stimulus fund to replace the Interstate 85 Yadkin River bridge.

Dollars Per Person

Staff writer Ann Doss Helms contributed.

Stimulus money goes where the people aren’t (NYT)

Stimulus money goes where the people aren't (NYT)

BY MICHAEL COOPER AND GRIFF PALMER – THE NEW YORK TIMES

Published: Thu, Jul. 09, 2009 04:53AM

Two-thirds of the U.S. population lives in large metropolitan areas, home to the nation's worst traffic jams and some of its oldest roads and bridges. But cities and their surrounding regions are getting far less than two-thirds of federal transportation stimulus money.

According to an analysis by The New York Times of 5,274 transportation projects approved so far — the most complete look yet at how states plan to spend their stimulus money — the 100 largest metropolitan areas are getting less than half the money from the biggest pot of transportation stimulus money. In many cases, they have lost a tug of war with state lawmakers that urban advocates say could hurt the nation's economic engines.

The stimulus law provided $26.6 billion for highways, bridges and other transportation projects but left the decision on how to spend most of it to the states, which have a long history of giving short shrift to major metropolitan areas when it comes to dividing federal transportation money. Now that all 50 states have beat a June 30 deadline by winning approval for projects that will use more than half of that transportation money, worth $16.4 billion, it is clear that the stimulus

“If we're trying to recover the nation's economy, we should be focusing where the economy is, which is in these large areas,” said Robert Puentes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution's Metropolitan Policy Program, which advocates more targeted spending. “But states take this peanut-butter approach, taking the dollars and spreading them around very thinly, rather than taking the dollars and concentrating them where the most complex transportation problems are.”

The 100 largest metropolitan areas also contribute three-quarters of the nation's economic activity, and one consequence of that is monumental traffic jams. A study of congestion in urban areas released Wednesday by the Texas Transportation Institute found that traffic jams in 2007 cost urban Americans 2.8 billion gallons of wasted gas and 4.2 billion hours of lost time.

The Times analysis shows that a little more than half of the stimulus money will be spent on “pavement improvement” projects, mostly repaving rutted and potholed roads. Nearly one-tenth of it will be spent to fix or replace bridges. More than a quarter of the money will be spent to widen roads or build new roads or bridges.

But the projects also offered vivid evidence that metropolitan areas are losing the struggle for stimulus money. Seattle found itself shut out when lawmakers in the state of Washington divided the first pot of stimulus money. Missouri has directed nearly half its money to 89 small counties that, together, comprise only a quarter of the state's population. The U.S. Conference of Mayors, which did its own analysis of different data in June, concluded that the nation's metropolitan areas were being “shortchanged.”

Pat McCrory, the mayor of Charlotte, N.C., complained that his city “did pretty terrible” when it came to getting money. Of the $423 million in projects approved so far in North Carolina, only $7.8 million is going to Mecklenburg County, the state's most populous county and the home of Charlotte.

Cleveland was initially promised $200 million of Ohio's stimulus money to help build a five-lane bridge to replace the 50-year-old Innerbelt Bridge, which is so deteriorated that officials banned heavy truck traffic on it last fall. But state officials, worried about meeting federal deadlines, took back $115 million in stimulus money and decided to use it on shovel-ready projects elsewhere.

Transportation experts said the stimulus is drawing attention to a longstanding trend.

“We have a long history of shortchanging cities and metropolitan areas and allocating transportation money to places where few people live,” said Owen D. Gutfreund, an assistant professor of urban planning at the City University of New York who wrote “20th Century Sprawl: Highways and the Reshaping of the American Landscape.”

Gutfreund said that in some states the distribution was driven by statehouse politics, with money spread to the districts of as many lawmakers as possible, or given out as political favors. In others, he said, the money is distributed by formulas that favor rural areas or that give priority to state-owned roads, often found far outside of urban areas.

Mayors had lobbied Congress to send the money directly to cities, but in the end, 70 percent of the money was sent to the states to be divided, and 30 percent was sent to metropolitan planning organizations, which represent the local governments in many metropolitan areas.

Those organizations were not bound by the June 30 deadline for getting their projects approved, so metropolitan areas could eventually see their share of the transportation money go up. Other pots of money in the transportation bill stand to benefit metropolitan areas more, including the $8.4 billion for mass transit and the $1.5 billion that the U.S. Transportation Department can award to projects of national or regional importance.

###

Cities fear loss of privilege tax (N&O)

Cities fear loss of privilege tax (N&O)

BY MARK SCHULTZ, Staff writer

CHAPEL HILL – Local governments are watching anxiously as state lawmakers consider eliminating one of their revenue streams. It's called the privilege license tax, a fee that businesses pay for the privilege of operating within a local government's jurisdiction.

Some lawmakers say the state needs to replace an unfair hodge-podge of fees that differ by locale and businesses without clear reason.

Local government officials and even some business advocates, however, say now is not the time to tinker with cash-strapped local budgets.

The N.C. Metropolitan Mayors Coalition has told local governments to oppose eliminating the tax, which generated $54.7 million in the last fiscal year for municipal governments across North Carolina, according to state legislative staff.

“At a time when cities are hurting economically and have already adopted their budgets, the loss of the privilege tax will result in a loss of services,” said Julie White, the coalition director.

“Local governments already have very limited local taxing options,” she said. “Why would they take away one of the few tools they have?”

Sen. David Hoyle, co-chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, said it's too soon to say whether the tax will be eliminated. But if it is, he said, new taxes on services would cover any losses.

“Local governments wouldn't lose any money,” said Hoyle, a Gaston County Democrat. “They'd gain money. … We're a service economy now.”

Local government leaders across the Triangle aren't so sure.

“We're concerned any time they talk about taking away part of our revenue,” said Ken Pennoyer, director of business management for Chapel Hill. “It's kind of a strange proposal. I'm not sure how this helps.”

Chapel Hill, with a small commercial tax base and a maximum $300 privilege license tax, projects making $110,000 from the tax this fiscal year, Pennoyer said.

In Durham and Raleigh, where revenue from the tax approaches 2 cents on both cities' tax rates, the stakes are much higher.

This year the tax is projected to bring in $2.75 million in Durham, interim finance director Keith Hermann said.

In Raleigh, the tax generates about $7 million, chief financial officer Perry James said.

Legislative staff members are analyzing how broadening the tax base and eliminating privilege license taxes would affect local governments.

Lawmakers want to simplify the tax structure and eliminate a “hodgepodge of authority” filled with inequities between businesses and between cities, said Sabra Faires, the Senate tax attorney.

“The goal in the end is not to have cities lose any money,” she said. “They'll get it in other ways than they get it now. That's the theory. The details aren't nailed down.”

Those details concern financial officers such as Raleigh's James.

“The [expanded] sales tax would supply some additional revenues,” he said. “But it's an untested revenue source.”

If lawmakers want to simplify taxes, they can do it other ways, James said, such as basing all levies on gross sales. Some privilege taxes are now based on types of businesses or their physical size.

“There's absolutely an argument to do away with the inequities,” he said. “I don't know that means getting rid of the tax.”

[email protected] or 919-932-2003

###

Shifting secondary road costs to cities, counties no solution

Shifting secondary road costs to cities, counties no solution

Proposal would put an unfunded mandate on local governments.

Posted: Wednesday, Jul. 01, 2009

From Durham Mayor Bill Bell and High Point Mayor Rebecca Smothers, co-chairs of the N.C. Metropolitan Mayors Coalition transportation committee, in response to “Let counties, cities control their roads,” by Sens. Dan Clodfelter and Bob Rucho.

(June 17 Viewpoint):

The state is in a budget crisis. We all understand that some changes must occur. But shifting the state's responsibility to local government is not the solution to the state's transportation funding problems.

Senate Bill 748 sponsored by Sens. Clodfelter and Rucho would do just that. The bill would transfer nearly 80 percent of the state's roads to cities and counties.

Sens. Clodfelter and Rucho wrote recently that the best way to improve the quality of the state's secondary road system (some 64,000 miles) is to transfer the responsibility for construction and maintenance to municipal and county governments. The remaining 15,000 miles of the state system – including the interstates, urban loops and primary roads – would remain under the NCDOT.

The senators tell us that this shift would improve the overall quality of the total system. What it would actually do is force counties into the “road business” and potentially establish 100 county transportation departments, thereby losing efficiencies we gain through one state DOT. It would require that both county and municipal governments assume responsibility for a system that the senators wrote “is crumbling under its own size and weight.”

On the surface you might think the senators' plan sounds good. But the senators themselves said the funds to care for these roads are increasingly inadequate. Ask yourself, if the state had the money to properly care for these roads, why would they be proposing to transfer them to local government? Let us explain why municipal governments are objecting to the increased responsibility.

The state collects a gas tax at the pump for road construction and maintenance and passes some of it through to cities for the 21,332 miles cities currently have responsibility for. But these pass-through revenues only cover half the total spent on city-maintained roads annually. The rest of the costs are funded by local city taxes. North Carolina has the highest gas tax in the Southeast and yet the per-person highway expenditures are only average for the Southeast. Is it fair to require additional local property taxes to support a new unfunded or underfunded mandate that the N.C. citizen has already paid for at the pump?

Local governments want good roads for our citizens and we want to partner with the state to find real solutions for our state's transportation problems. We want to be part of a discussion that begins to chart a new and positive course for the future of transportation in North Carolina. But transferring 64,000 miles of road responsibility to another level of government during these trying economic times is NOT the place to start.

###

Road responsibility

Road responsibility

JOURNAL EDITORIAL STAFF

Published: May 12, 2009

For 80 years, state government has planned, designed, built and maintained almost all of North Carolina's roads and highways. Unless individual counties or municipalities pursue responsibility for their own roads, this system should not change.

Bills in the General Assembly would shift responsibility to local governments in several different ways. One would do so outright, another with limits.

During the Great Depression, legislators understood that the economy of the state depended on good roads. Although no one was flush at the time, the state was in much better financial position than were local governments to pay for roads. So, in what is still considered one of the most progressive steps taken by any state government at the time, North Carolina took responsibility for almost all of its roads.

Today there are 79,000 state-maintained roads in North Carolina, one of the largest such systems in America. But our roads are hurting because the legislature has shown a favoritism to rural areas. The state's urban areas, which have the most traffic, are not getting as much of the revenue as they need to keep up with growth and maintenance demands.

Those problems do not warrant a dismantling of the current system. It still works. North Carolina needs good roads in every community.

Gov. Bev Perdue has already taken one very important step toward improving the state's transportation system. She has taken most decision-making power away from the politically charged Board of Transportation. The legislature could fix the rest of the problems by directing state revenues to projects in the areas with the most traffic.

Creating a patchwork of local systems would not solve our problems.

There are times when state control of the roads is not beneficial. Individual communities often chafe at having to work with the department of transportation on road projects that are very local in nature.

If the people of a community want to take control of their roads, then there should be something in state law that would allow them to do so.

That way, road decisions in many communities would be integrated into other development plans in ways that would allow local leaders the most options.

Of course, if local governments take responsibility for their roads, they must also get some of the local road tax revenues.

North Carolina has been well served by state control of transportation. With some requested exceptions allowed, it should continue with that system.

###